China’s Social Credit System: Using Data Science to Rebuild Trust in Chinese Society by Jason Hunsberger

From 1966-1976 Mao Zedong and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) waged an idological war on its own citizens. Seeking to purge the country of “bourgeois” and “insufficiently revolutionary” elements, Mao closed the schools and set an army of high school and university students on the populace. The ensuing cultural strife placed neighbor against neighbor, young against old, and destroyed families. Hundreds of thousands died.

Forty years later, China is still trying to recover from the social damage. Facing widespread issues of government and corporate corruption, and lack of respect for the rule of law, the national party is seeking to transform Chinese society to be more “sincere”, “moral”, and “trustworthy.” The means by which the CCP seeks to do this is by creating a nationwide social credit system. Formally launched in 2014 after two decades of research and development, this system’s stated goal is:

“allow the trustworthy to roam everywhere under heaven while making it hard for the discredited to take a single step.”

NOTE: Under heaven is a rough translation of one of the historical names of China.

Image 1: Goals of China’s social credit system as found in the Chinese news media (Source: MERICS)

Image 1: Goals of China’s social credit system as found in the Chinese news media (Source: MERICS)

By 2020, China hopes to have the system fully deployed across the entire country.

How will this nationwide social credit system help the nation rebuild trust in its public and private institutions and its people? By using data science to analyze all aspects of public life. That will be used to create a social credit score that represents a citizen’s or a company’s contribution to society. If your actions are a detriment to society, your social credit score will go down. If your actions are beneficial to society, your score will go up. Depending upon your credit score, you will either be restricted from aspects of society or be granted access to certain benefits.

The social credit system is deeply integrated into local government databases and large technology companies. It collects data from automatic facial recognition cameras deployed at city intersections, video game systems, search engines, financial systems, social media, political and religious groups you engage in, and more. With all this data, the social credit system creates a universal social credit score which can be integrated into all aspects of Chinese life.

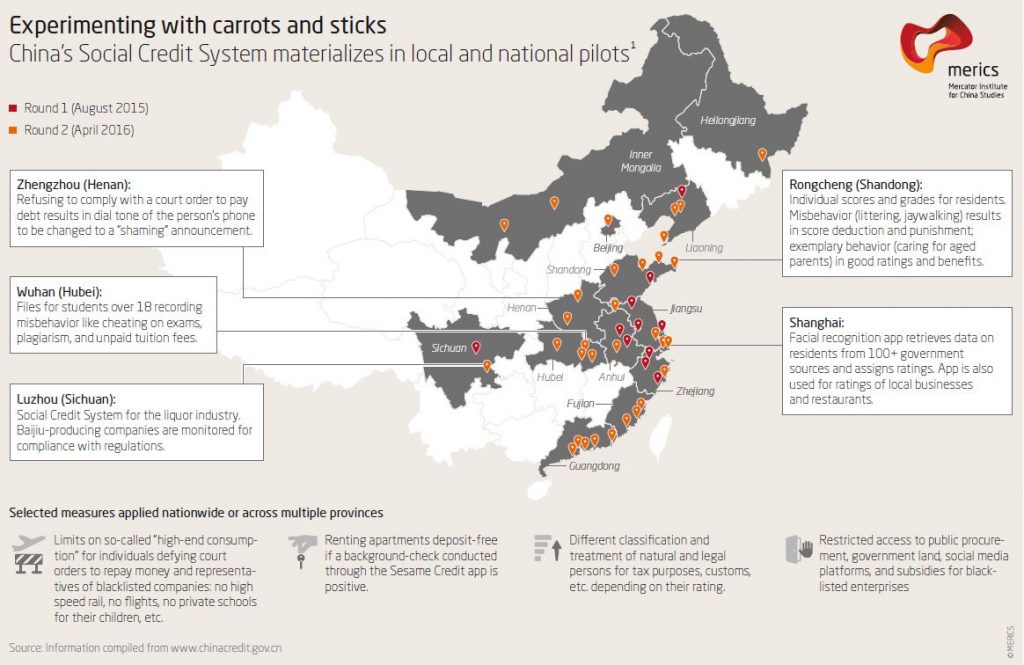

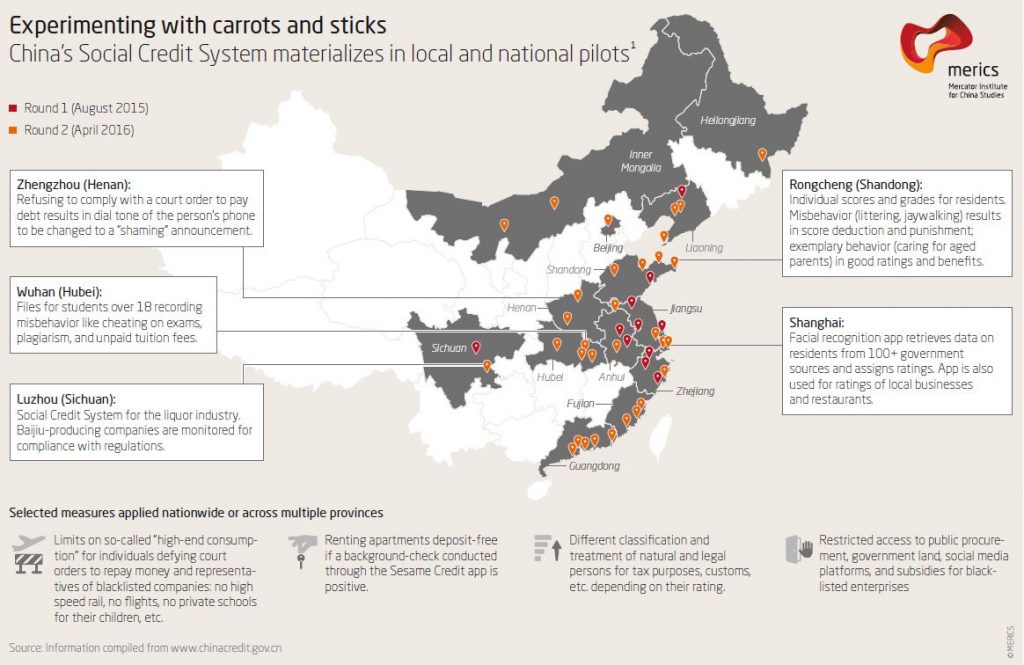

Beyond a mere pipedream, there are currently 36 pilot programs deployed in some of China’s largest cities.

Image 2: A map of the social credit pilot cities in China (Source: MERICS)

Image 2: A map of the social credit pilot cities in China (Source: MERICS)

Here are some examples of the social credit system at work, collected from these pilot programs:

- you wake up in the morning to find your face, name, and home address being placed on a billboard in your local neighborhood saying that you have a negative impact on society.

- the ringtone on your phone is automatically changed so that all callers know that you have not paid a bill.

- your girlfriend/boyfriend dumps you because your social credit score is integrated into your dating app.

Image 3: A cartoon on Credit China’s website on the impact of the social credit system on one’s dating life (Source: MERICS)

Image 3: A cartoon on Credit China’s website on the impact of the social credit system on one’s dating life (Source: MERICS)

- your company is restricted from public procurement systems and access to government land

- you fly to a destination for business, but are unable to take your return flight because your social credit score decreased

- you work for a business that gets punished for unscrupulous behavior and you are unable to move to another company because you are held responsible for the company’s behavior.

- your company is blocked from having access to various government subsidies

- you are able to rent apartments with no deposit, or rent bikes for 1.5 hours for free, while others have to pay extra.

- you try to get away for that long awaited vacation only to find that you cannot fly or take the high-speed train to any of your desired destinations.

- your company may not be allowed to participate on social media platforms

- your academic performance, including whether you cheated on an exam or plagarized a paper can affect your social credit score

If that is not enough, anyone who runs afoul of the credit system will have their personal information added to a blacklist which is published in a searchable public database and on major news websites. This public shaming is considered a feature rather than a flaw of the system.

Image 4: A public billboard in Rongcheng showing citizens being shamed as a result of their social credit scores (SOURCE: Foreign Policy)

Image 4: A public billboard in Rongcheng showing citizens being shamed as a result of their social credit scores (SOURCE: Foreign Policy)

Obviously, the entire social credit system raises many issues. China is making a big bet that the citizenry will view this data collection, analysis, and scoring positively. To help, the Chinese government and national media have been actively promoting “big data-driven technological monitoring as providing objective, irrefutable measures of reality.” This approach seems to ignore the many issues present in information systems regarding the bias of categories and of the algorithms used to analyze the data these systems contain. Additionally, it fails to address the problems with erroneous data falsely rendering damaging reputational judgements against the people.

But putting aside weather or not these systems can measure what they seek to reliably, does creating a vast technological data collection system that is deeply integrated into all aspects of people’s lives and is used to calculate a single ‘trustworthiness’ score that is to be displayed publicly if the score is too low, sound like actions that are intended to build trust amongst people? On its face, it does not. It sounds more like a system built to control people. And systems that are built to control people, at their heart, do not trust the people they are trying to control. For if the people could be trusted to make the decisions that were good for society, why would such a system be needed in the first place? So, fundamentally, can the CCP build trust with its citizens by taking an action that loudly tells them that they don’t trust them? Will a system built on distrust foster trust amongst the populace? Or will it signal to the entire populace that their fellow citizens, neighbors, friends, and family members might not be trustworthy? Instead of promoting trust within society, it is very possible that China’s social credit system will actually further erode trust in China’s society.

References

Ohlberg, Mareike, Shazeda Ahmed, Bertram Lang. “Central Planning, Local Experiments: The complex implementation of China’s Social Credit System.” Mercator Institute for China Studies, December 12, 2017:

https://www.merics.org/sites/default/files/2017-12/171212_China_Monitor_43_Social_Credit_System_Implementation.pdf

Mistreanu, Simina. “Life Inside China’s Social Credit Laboratory.” Foreign Policy, April 3, 2018:

https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/04/03/life-inside-chinas-social-credit-laboratory/

Greenfeld, Adam. “China’s Dystopian Tech Could be Contagious.” The Atlantic, February 14, 2018:

https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/02/chinas-dangerous-dream-of-urban-control/553097/

Image 1: Goals of China’s social credit system as found in the Chinese news media (Source: MERICS)

By 2020, China hopes to have the system fully deployed across the entire country.

How will this nationwide social credit system help the nation rebuild trust in its public and private institutions and its people? By using data science to analyze all aspects of public life. That will be used to create a social credit score that represents a citizen’s or a company’s contribution to society. If your actions are a detriment to society, your social credit score will go down. If your actions are beneficial to society, your score will go up. Depending upon your credit score, you will either be restricted from aspects of society or be granted access to certain benefits.

The social credit system is deeply integrated into local government databases and large technology companies. It collects data from automatic facial recognition cameras deployed at city intersections, video game systems, search engines, financial systems, social media, political and religious groups you engage in, and more. With all this data, the social credit system creates a universal social credit score which can be integrated into all aspects of Chinese life.

Beyond a mere pipedream, there are currently 36 pilot programs deployed in some of China’s largest cities.

Image 1: Goals of China’s social credit system as found in the Chinese news media (Source: MERICS)

By 2020, China hopes to have the system fully deployed across the entire country.

How will this nationwide social credit system help the nation rebuild trust in its public and private institutions and its people? By using data science to analyze all aspects of public life. That will be used to create a social credit score that represents a citizen’s or a company’s contribution to society. If your actions are a detriment to society, your social credit score will go down. If your actions are beneficial to society, your score will go up. Depending upon your credit score, you will either be restricted from aspects of society or be granted access to certain benefits.

The social credit system is deeply integrated into local government databases and large technology companies. It collects data from automatic facial recognition cameras deployed at city intersections, video game systems, search engines, financial systems, social media, political and religious groups you engage in, and more. With all this data, the social credit system creates a universal social credit score which can be integrated into all aspects of Chinese life.

Beyond a mere pipedream, there are currently 36 pilot programs deployed in some of China’s largest cities.

Image 2: A map of the social credit pilot cities in China (Source: MERICS)

Here are some examples of the social credit system at work, collected from these pilot programs:

Image 2: A map of the social credit pilot cities in China (Source: MERICS)

Here are some examples of the social credit system at work, collected from these pilot programs:

Image 3: A cartoon on Credit China’s website on the impact of the social credit system on one’s dating life (Source: MERICS)

Image 3: A cartoon on Credit China’s website on the impact of the social credit system on one’s dating life (Source: MERICS)

Image 4: A public billboard in Rongcheng showing citizens being shamed as a result of their social credit scores (SOURCE: Foreign Policy)

Obviously, the entire social credit system raises many issues. China is making a big bet that the citizenry will view this data collection, analysis, and scoring positively. To help, the Chinese government and national media have been actively promoting “big data-driven technological monitoring as providing objective, irrefutable measures of reality.” This approach seems to ignore the many issues present in information systems regarding the bias of categories and of the algorithms used to analyze the data these systems contain. Additionally, it fails to address the problems with erroneous data falsely rendering damaging reputational judgements against the people.

But putting aside weather or not these systems can measure what they seek to reliably, does creating a vast technological data collection system that is deeply integrated into all aspects of people’s lives and is used to calculate a single ‘trustworthiness’ score that is to be displayed publicly if the score is too low, sound like actions that are intended to build trust amongst people? On its face, it does not. It sounds more like a system built to control people. And systems that are built to control people, at their heart, do not trust the people they are trying to control. For if the people could be trusted to make the decisions that were good for society, why would such a system be needed in the first place? So, fundamentally, can the CCP build trust with its citizens by taking an action that loudly tells them that they don’t trust them? Will a system built on distrust foster trust amongst the populace? Or will it signal to the entire populace that their fellow citizens, neighbors, friends, and family members might not be trustworthy? Instead of promoting trust within society, it is very possible that China’s social credit system will actually further erode trust in China’s society.

References

Ohlberg, Mareike, Shazeda Ahmed, Bertram Lang. “Central Planning, Local Experiments: The complex implementation of China’s Social Credit System.” Mercator Institute for China Studies, December 12, 2017: https://www.merics.org/sites/default/files/2017-12/171212_China_Monitor_43_Social_Credit_System_Implementation.pdf

Mistreanu, Simina. “Life Inside China’s Social Credit Laboratory.” Foreign Policy, April 3, 2018: https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/04/03/life-inside-chinas-social-credit-laboratory/

Greenfeld, Adam. “China’s Dystopian Tech Could be Contagious.” The Atlantic, February 14, 2018: https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/02/chinas-dangerous-dream-of-urban-control/553097/

Image 4: A public billboard in Rongcheng showing citizens being shamed as a result of their social credit scores (SOURCE: Foreign Policy)

Obviously, the entire social credit system raises many issues. China is making a big bet that the citizenry will view this data collection, analysis, and scoring positively. To help, the Chinese government and national media have been actively promoting “big data-driven technological monitoring as providing objective, irrefutable measures of reality.” This approach seems to ignore the many issues present in information systems regarding the bias of categories and of the algorithms used to analyze the data these systems contain. Additionally, it fails to address the problems with erroneous data falsely rendering damaging reputational judgements against the people.

But putting aside weather or not these systems can measure what they seek to reliably, does creating a vast technological data collection system that is deeply integrated into all aspects of people’s lives and is used to calculate a single ‘trustworthiness’ score that is to be displayed publicly if the score is too low, sound like actions that are intended to build trust amongst people? On its face, it does not. It sounds more like a system built to control people. And systems that are built to control people, at their heart, do not trust the people they are trying to control. For if the people could be trusted to make the decisions that were good for society, why would such a system be needed in the first place? So, fundamentally, can the CCP build trust with its citizens by taking an action that loudly tells them that they don’t trust them? Will a system built on distrust foster trust amongst the populace? Or will it signal to the entire populace that their fellow citizens, neighbors, friends, and family members might not be trustworthy? Instead of promoting trust within society, it is very possible that China’s social credit system will actually further erode trust in China’s society.

References

Ohlberg, Mareike, Shazeda Ahmed, Bertram Lang. “Central Planning, Local Experiments: The complex implementation of China’s Social Credit System.” Mercator Institute for China Studies, December 12, 2017: https://www.merics.org/sites/default/files/2017-12/171212_China_Monitor_43_Social_Credit_System_Implementation.pdf

Mistreanu, Simina. “Life Inside China’s Social Credit Laboratory.” Foreign Policy, April 3, 2018: https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/04/03/life-inside-chinas-social-credit-laboratory/

Greenfeld, Adam. “China’s Dystopian Tech Could be Contagious.” The Atlantic, February 14, 2018: https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/02/chinas-dangerous-dream-of-urban-control/553097/