Social Credit: a Chinese experiment by Yang Yang Qian

Imagine applying for a loan, but first the bank must check your Facebook profile for a credit report. As odd as it feels for consumers in the United States, for consumers in China, this is already part of an experiment with social credit.

The Chinese government has had

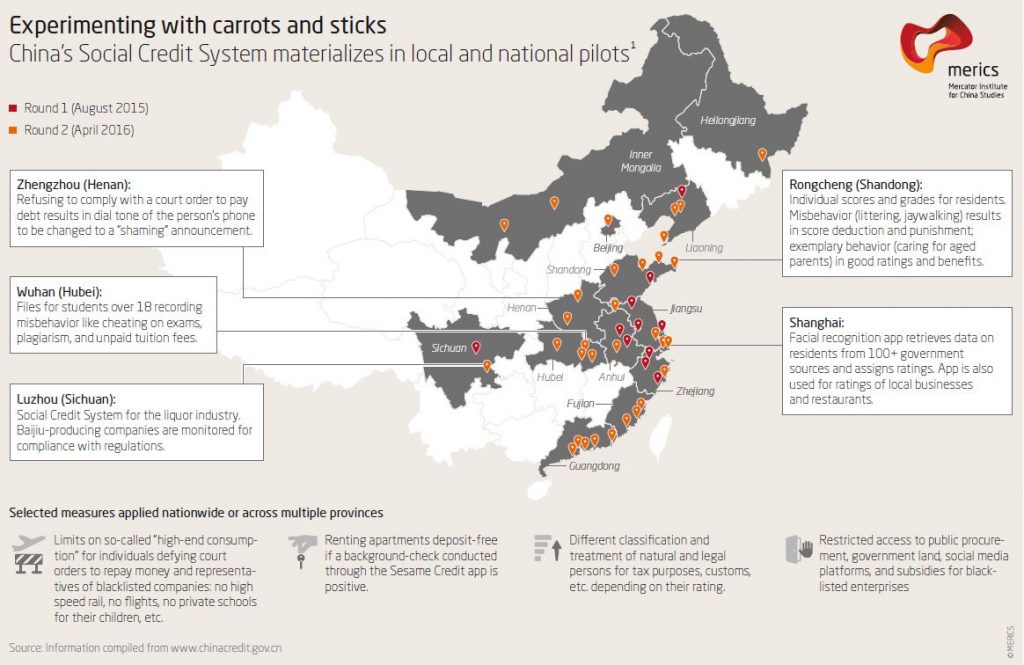

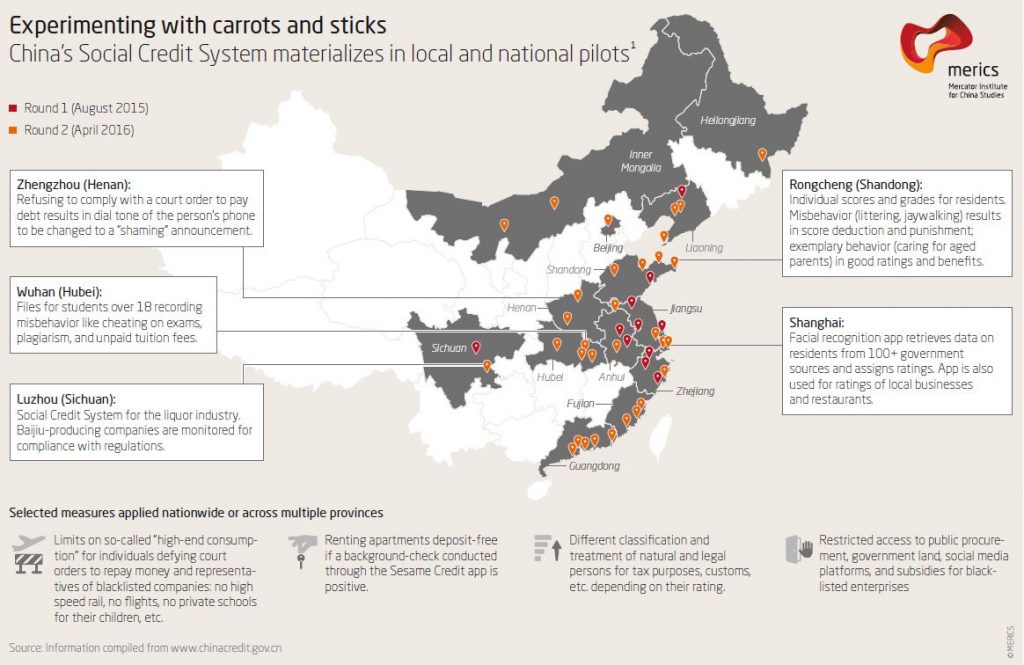

plans to implement a Social Credit System by 2020: a big data approach to regulating the behavior of individuals, companies, and other institutions such as NGOs. Essentially, under the Social Credit System, a company or individual would be given a set of ratings that summarizes how good behaving they are in various categories, such as propensity for major credit offenses. The platform is intended to aggregate a huge amount of data about the companies and individuals. This includes general information, compliance records, and even real-time data where possible. Eventually, the system will span both government data sources and incorporate commercial sources. If the platform can be implemented successfully, it should strengthen the Chinese government’s ability to enforce regulations and policies. Now, the system is not yet in place. Instead, the government has licensed private companies and some municipal governments to build their own social credit systems as pilot programs. One of the higher profile projects is Alibaba’s Sesame Credit.

As individual consumers in the United States, many of us are used to having personal credit scores. With the Social Credit System, however, it looks to be much more comprehensive. One key difference is that the scope of the system intends to cover all “market participants”. Both individuals and companies are subject to it. For instance, some of more ambitious objectives aim to track polluting companies through their real-time emissions records. Moreover, the stated focus of the system is to promote best practices in the marketplace.

Proponents argue that such a system will help China overcome a multitude of societal ills: food safety scandals, public corruption, and tax evasion.

But on the other side of the coin, there are fears that such a system can be used as a mass disciplinary machine targeted at the citizenry. A good rating might allow users to borrow favorably on credit or find a good deal through Alibaba’s hotel partners. A bad rating might bar them from traveling. For instance, nine million low-score users found were

barred from buying domestic plane tickets. With these risks for material harm on the mind, some have voiced fears that certain activities might be promoted or punished, a sort of subtle social coercion. Part of the problem is Alibaba isn’t too clear about the specific actions will be punished. On the one hand, they’ve released some high-level descriptions of the categories they score: credit history, online behavior, ability to fulfill contracts, personal profile completeness, and interpersonal relationships. On the other hand, the BBC

reported that Sesame Credit makes no secret they will punish specific online behaviors:

“Someone who plays video games for 10 hours a day, for example, would be considered an idle person, and someone who frequently buys diapers would be considered as probably a parent, who on balance is more likely to have a sense of responsibility,” Li Yingyun, Sesame’s technology director told Caixin, a Chinese magazine, in February.

Perhaps Sesame Credit just used this as an evocative example, or perhaps they meant it in all earnestness. In any case, the fact that a large private conglomerate, with encouragement from a government, is essentially piloting an opaque algorithm to enforce good behavior did

not sit well with some human rights watch groups. And rather alarmingly, some of the current scoring systems supposedly also adjusts an individual’s scores based on the behaviors their social circle. This might encourage use of social pressure to turn discontents, into compliant citizens. Are we looking at the prototype for a future government social credit system that will leverage social pressure for mass citizen surveillance? Some sort of Scarlet Letter, meets Orwellian dystopia?

Wait. There is probably a too much alarmist speculation about the Social Credit System in Western media right now. As usual, there is a lot of nuance and context surrounding this experiment. After all, the large central system envisioned by Beijing is not yet implemented. The social credit platforms that do exist are either separate pilots run by local municipal governments, or by private companies like Alibaba or Tencent. We should also keep in mind that the current Sesame Credit system, along with its peculiarities, is designed to

reward loyal Alipay users, instead of some abstract “citizen trustworthiness”. In Chinese media, citizens seem to be generally see the need for a social credit system. Additionally, there is an active media discussion within China about specific concerns, such as the risk for privacy invasions by the companies that host the data, or opinions on what kinds of data should be used to calculate the scores. It remains to be seen if the central government system will want to adopt any of the features of these pilot programs, and how much leeway it will allow for those companies to continuing this

experiment.

Imagine applying for a loan, but first the bank must check your Facebook profile for a credit report. As odd as it feels for consumers in the United States, for consumers in China, this is already part of an experiment with social credit.

The Chinese government has had plans to implement a Social Credit System by 2020: a big data approach to regulating the behavior of individuals, companies, and other institutions such as NGOs. Essentially, under the Social Credit System, a company or individual would be given a set of ratings that summarizes how good behaving they are in various categories, such as propensity for major credit offenses. The platform is intended to aggregate a huge amount of data about the companies and individuals. This includes general information, compliance records, and even real-time data where possible. Eventually, the system will span both government data sources and incorporate commercial sources. If the platform can be implemented successfully, it should strengthen the Chinese government’s ability to enforce regulations and policies. Now, the system is not yet in place. Instead, the government has licensed private companies and some municipal governments to build their own social credit systems as pilot programs. One of the higher profile projects is Alibaba’s Sesame Credit.

As individual consumers in the United States, many of us are used to having personal credit scores. With the Social Credit System, however, it looks to be much more comprehensive. One key difference is that the scope of the system intends to cover all “market participants”. Both individuals and companies are subject to it. For instance, some of more ambitious objectives aim to track polluting companies through their real-time emissions records. Moreover, the stated focus of the system is to promote best practices in the marketplace. Proponents argue that such a system will help China overcome a multitude of societal ills: food safety scandals, public corruption, and tax evasion.

But on the other side of the coin, there are fears that such a system can be used as a mass disciplinary machine targeted at the citizenry. A good rating might allow users to borrow favorably on credit or find a good deal through Alibaba’s hotel partners. A bad rating might bar them from traveling. For instance, nine million low-score users found were barred from buying domestic plane tickets. With these risks for material harm on the mind, some have voiced fears that certain activities might be promoted or punished, a sort of subtle social coercion. Part of the problem is Alibaba isn’t too clear about the specific actions will be punished. On the one hand, they’ve released some high-level descriptions of the categories they score: credit history, online behavior, ability to fulfill contracts, personal profile completeness, and interpersonal relationships. On the other hand, the BBC reported that Sesame Credit makes no secret they will punish specific online behaviors:

Imagine applying for a loan, but first the bank must check your Facebook profile for a credit report. As odd as it feels for consumers in the United States, for consumers in China, this is already part of an experiment with social credit.

The Chinese government has had plans to implement a Social Credit System by 2020: a big data approach to regulating the behavior of individuals, companies, and other institutions such as NGOs. Essentially, under the Social Credit System, a company or individual would be given a set of ratings that summarizes how good behaving they are in various categories, such as propensity for major credit offenses. The platform is intended to aggregate a huge amount of data about the companies and individuals. This includes general information, compliance records, and even real-time data where possible. Eventually, the system will span both government data sources and incorporate commercial sources. If the platform can be implemented successfully, it should strengthen the Chinese government’s ability to enforce regulations and policies. Now, the system is not yet in place. Instead, the government has licensed private companies and some municipal governments to build their own social credit systems as pilot programs. One of the higher profile projects is Alibaba’s Sesame Credit.

As individual consumers in the United States, many of us are used to having personal credit scores. With the Social Credit System, however, it looks to be much more comprehensive. One key difference is that the scope of the system intends to cover all “market participants”. Both individuals and companies are subject to it. For instance, some of more ambitious objectives aim to track polluting companies through their real-time emissions records. Moreover, the stated focus of the system is to promote best practices in the marketplace. Proponents argue that such a system will help China overcome a multitude of societal ills: food safety scandals, public corruption, and tax evasion.

But on the other side of the coin, there are fears that such a system can be used as a mass disciplinary machine targeted at the citizenry. A good rating might allow users to borrow favorably on credit or find a good deal through Alibaba’s hotel partners. A bad rating might bar them from traveling. For instance, nine million low-score users found were barred from buying domestic plane tickets. With these risks for material harm on the mind, some have voiced fears that certain activities might be promoted or punished, a sort of subtle social coercion. Part of the problem is Alibaba isn’t too clear about the specific actions will be punished. On the one hand, they’ve released some high-level descriptions of the categories they score: credit history, online behavior, ability to fulfill contracts, personal profile completeness, and interpersonal relationships. On the other hand, the BBC reported that Sesame Credit makes no secret they will punish specific online behaviors: